Community Changemakers

Ricardo Flores of LISC San Diego

This conversation is part of our Community Changemaker Series. Build It Green is talking to people who are tackling climate change, addressing social inequity, and revitalizing communities through their work in the residential building sector. These innovators demonstrate what outcomes are possible when you think beyond a single problem and consider more multifaceted solutions. In highlighting these leaders and their work, we aim to spark ideas, drive discussions, and inspire others to engage and take action.

Ricardo Flores, Executive Director

Background

Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) San Diego is a non-profit funding agency that takes a community- and partnership-driven approach to revitalizing neighborhoods. We recently had the pleasure of meeting with Ricardo Flores, Executive Director and a long-time San Diego resident, to discuss their work.

Despite Ricardo’s unconventional path to the housing realm—some of his early work involves the film industry and the movie Shrek 2—he has always been a strong community advocate. Prior to his current role, he worked as an aide for Congresswoman Susan Davis, served as Chief of Staff for Congressmember Emerald, and dedicated his time to participating in advisory boards, committees, and volunteering efforts.

Through the Black Homebuyers Program, LISC San Diego has provided grants to help 19 Black families with low-to-medium incomes cover down payments or closing costs on their first homes. It was an honor to speak with Ricardo about this initiative and some of the big questions it starts to answer—namely, how can we address the lasting impacts of redlining and shape communities that accommodate for everyone’s growth?

Listen to our conversation or check out the full transcript (with timestamps) below!

Full Transcript

Ricardo (00:33): Our partners at The San Diego Foundation and Union Bank… They had come together to create a Black homebuyer program. And the foundation—the San Diego Foundation, all credit to them, really. It was their inspiration. They created a Black investment committee after the death of George Floyd. They identified home ownership and then they put a million dollars in grants to that. They partnered with Union Bank to provide mortgages and then Union Bank would also provide a $9,000 grant. And then they came out to LISC and they said, we’d like to use your abilities to move money as a CDFI. So we launched in August and to date, we’ve gotten 19 individuals—Black families that are homeowners. The minimum down payment is $40,000 and then $9,000 with Union Bank. So it’s $49,000, and that’s it. There’s no recapture. There’s no lien on a home.

(01:25) There’s no nothing. It’s like a grant—a $49,000 grant from a family member—to help people get into home ownership. You know, many of our grantees are very small families, families of three or smaller, and they’ve all moved to condos. Only one is in a single family home. And so we have a need and a desire to build housing to meet their ability to get a mortgage. And because we’re a nonprofit, we want to think about this very holistically. And we could build in the communities of opportunity most likely, but would that be stretching their $49,000? Would that be really stretching that investment? And the answer is no, because there’s land in our communities that appreciates better. Appreciates quicker. Has better infrastructure, better schools. And so why can’t we build in those neighborhoods? And so what we’re trying to do now is in neighborhoods where you’re talking about a home that’s, you know, a million dollars average, we want to build a $500,000 home.

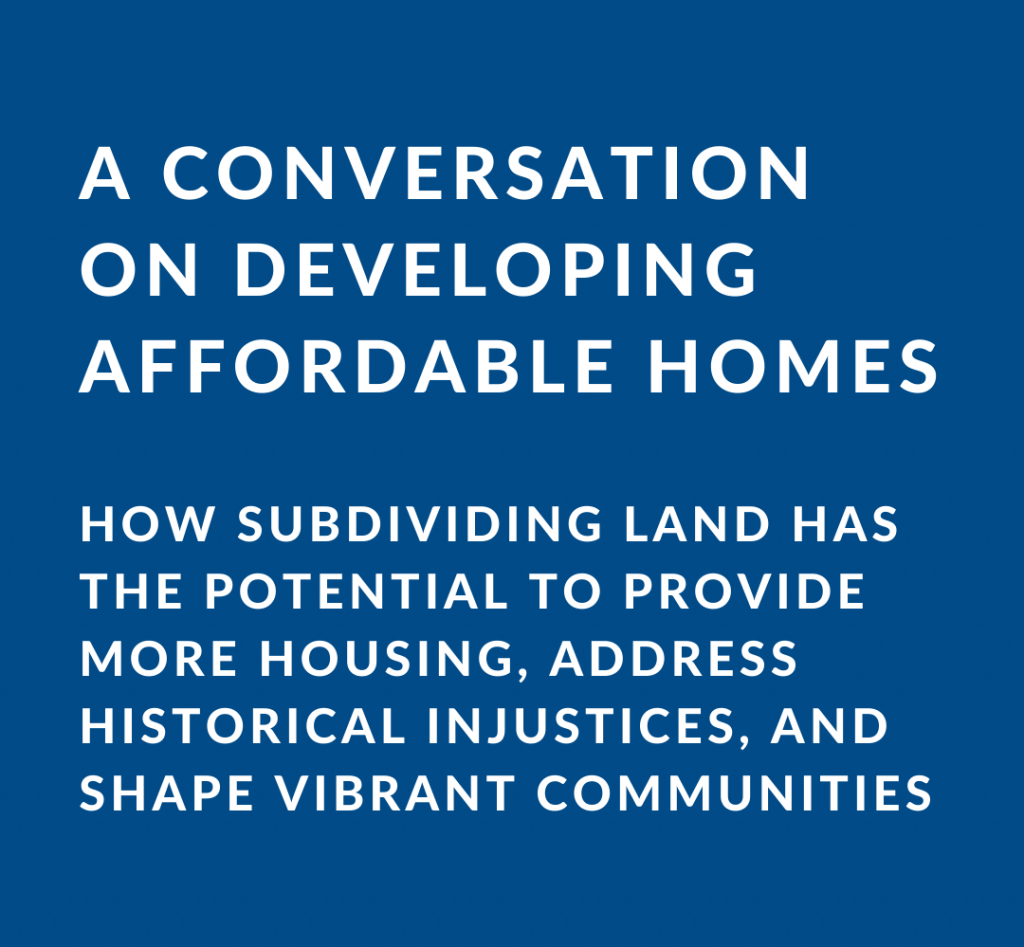

(02:27) And the way to do that is to subdivide the 5,000 or 7,000 square feet of land, currently in which a house sits right smack dab in the middle of all that land. I think all of us recognize that our communities are segregated. That, you know, I, I call it apartheid and I think that’s exactly what it is. Because it’s intentional. And we have to change that. because what we’re seeing is communities in which poverty continues to increase, communities where schools are not what they should be… You know, we’re seeing a lot of challenges in our country because certain communities are hogging all of the best infrastructure and the best land, and those communities in San Diego comprise of 53% of our city. 53% of our city is off limits to any new construction whatsoever. And that’s, that’s unacceptable. And it’s unsustainable. What’s even more frustrating is that, you know, for everyone listening, your local city councils have all the power to make those homes cheaper because they can reduce the value of the land by allowing us to purchase it at smaller increments. And so this idea that we’re all kind of banging our heads against the wall, asking how are we gonna make housing cheaper? We know how to do it.

Making communities more walkable and bikeable is key to reducing reliance on cars. Photo courtesy of tttuna on iStock.

LISC San Diego’s land subdivision approach allows them to build $500,000 homes in a market where the average home is nearly twice as expensive. Infographic created using Canva.

This condo complex is where the first recipient of the Black Homebuyer Program was able to purchase his own home. Photo taken by Cristina Kim, courtesy of KPBS.

Chloe (03:39): It’s complicated. And definitely there needs to be a, a big shift in how things are done today. That being said, communities everywhere are facing this complex web of issues. We’re faced with climate change, social inequity, and housing affordability crises. And in order to effectively tackle one, we definitely need to address them all. How do you see LISC San Diego operating at the intersection of these different issues, especially with your three focus areas: affordable housing, economic development, and capacity-building?

Ricardo (04:11): So, you know, we actually, we’ve been engaged with that conversation. We are part of our San Diego Green New Deal Coalition. We actually asked the group if they would be willing to entertain our idea of subdividing land and support it. And they said, yes, they would, and they are. Because if you have a dense enough community where you can live, walk and shop, then that allows you to get out of your car. I, for several years, lived in downtown San Diego with my wife. I did not, we didn’t get in a car on the weekends. In fact, I lived in downtown working for the city. I never drove my car. I just parked it, and pretty much that was it. Because we had everything there. We had movie theaters, we had grocery stores, we had restaurants, we had parks. We had places to exercise.

(04:55) We had all that, right? We have to be able to make communities like that everywhere. Maybe not downtowns, but just communities that have more things to do. And in fact, what’s interesting is if you ask most community people in San Diego, for sure, they want that. They want a local coffee shop. They want a local bookstore. They want their local restaurant. They want these things, to be able to get out of their car and move. But unless you have the density to support that, it’s not going to happen. And then the other thing, too, is that our climate colleagues are really interested in stopping sprawl. We, you know, we don’t disagree with it. Because you know, we don’t wanna put families way out there as well, because that destroys whatever infrastructure they have, they have to commute in, et cetera. But what we’re trying to do as well is to impress upon individuals that we can’t stop building in the back country until we can build in the urban core. That we have to be able to build in the urban core. Once we release those zoning restrictions, absolutely. We can start to look at how big do we wanna get as a, as a region.

For several years, I lived in downtown San Diego working for the city. I never drove my car. Because we had everything there. We had movie theaters, we had grocery stores, we had restaurants, we had parks. We had places to exercise. We have to be able to make communities like that everywhere.

Ricardo Flores, LISC San Diego Tweet

Chloe (05:59): Yeah, definitely. We know that LISC San Diego has helped fund and finance a number of community improvement projects, affordable homes and capacity-building programs. What are some of the barriers your organization regularly encounters in this work and what steps are necessary to address them? I know you’ve talked about it a little bit.

Ricardo (06:18) Yeah. So, you know, there again, I think people try to lump housing together, right? What we’re trying to do with our Black Homebuyer Program is to provide for, really, what is called middle income housing, right? It’s really housing that, I mean, teachers can’t afford right now in our community, right? Housing for $500,000. It seems so out of reach when the average home here is almost $800,000, right. Now, many of these people, I should stress, do have what people in business terms call cash flow, right? They have money coming in. It’s just so little, it doesn’t even sustain them to rent a place. So LISC tries to build to that population. And the challenge we face here, like a lot in San Diego is that our community doesn’t have its own supply of taxpayer dollars to build this housing. And I say this because what we do LISC is we’re financiers.

(07:06) We finance affordable housing. So how affordable housing gets built is in three steps. The first step is a pre-development loan. So you can buy a piece of land or buy a building and do your architectural drawings, your soil sampling, all of that. We provide that capital to affordable housing developers, for profit nonprofit. The next step is a construction loan. Once that land has been bought with our money and it’s been entitled, soil sampling has been done… The land now actually has real value to it because now everybody knows what you can do with this land. The developer can go to a bank and ask for a 20 million dollar construction loan because the collateral is that land, that, that we’ve provided the money for. That buys us out, and now this developer goes onto the construction phase. Well, the next question is—who buys this bank out?

(07:56) This bank just spent 20 million of (maybe it’s our money, because it’s maybe it’s our bank) to build this project. Somebody has to buy the bank out. Well that somebody is us, the taxpayer, because the financial markets cannot put money down on a building for the next 30 years and just wait patiently or maybe even forgive the debt. The taxpayer can. And so that’s where you have low-income housing tax credits. That’s where you have a community that has its own supply of patient money—30-to-40-year money, which will be most likely forgiven, right? Basically it’s a grant. That’s where that comes in. And in San Diego, we lack that last space of money. We definitely have money through the state. We definitely get money through the federal government. But we don’t have our own supply of cash that allows us to leverage state monies.

(08:48) And so that’s the real challenge in our market is that last piece, which is how do you keep it sustainable and buy out essentially the construction loan. Because when affordable housing developers start this really crazy process, oftentimes they’re starting off without having the last piece of financing. They only have this first piece. So they’re kind of getting their financing as they go along, but what they really need to know, and they really want to have is the support of a local community by having tax dollars out there for them to utilize, to leverage against low income housing tax credits. The other thing—which I think the state’s done actually a good job with—is they really have made affordable housing ministerial, which is a good thing. And I think we just have to continue, you know, allowing for these projects to be built in neighborhoods and, and not really… not really get so involved.

(09:41) And finally, I’ll share one quick story. Again, I lived in downtown for years, and my wife at one point, you know, because it’s a lot of homeless in downtown San Diego and they’ve always been there. And my wife was getting frustrated and I said, “well, if they just build a shelter…” And she said, “What? A shelter? That means that more people are gonna come.” And I said that we have a shelter in our neighborhood. We have a women’s shelter, a block away from us. She had no idea. She had no idea. And we walked by it. Again, this idea that for whatever reason, me, a private citizen, needs to know what’s going on behind that building because that building’s somehow affecting my life. No, it’s not. You know, because at the end of the day, again, we need to accommodate for different patterns of growth.

(10:23) And we also need to be able to create environments where people of different economic backgrounds and race and genders are all coming together. And again, I think with our Black Homebuyers Program, you know, one of the interesting things that I talk to folks about when I’m trying to raise additional grant dollars for it. (So if anybody’s listening! (laughs)) But I’m really always fascinated that people will say to us: what do you mean there’s no lien on the home, that they have to live there for five years… There’s no hoops that they have to jump through. You’re just gonna give them money, give people money? Yes. Yes. Because you know what? These people have credit scores, they have jobs, they have savings… but they cannot put the down payment down. And truth be told, they’re working in a market that not only is nonfunctional, but that is actually being mishandled or intentionally left more complicated.

(11:19) So I, I think it’s really frustrating. I am very grateful though, to the state and to folks—probably your groups and others that you guys know up there. So really just a lot of props to those activists, those leaders who really put teeth into this arena and really kind of forced a strong conversation. Because other than that, we wouldn’t be having this. We, it wouldn’t be the same. It wouldn’t be the same way. We would be saying, well, if the kid lives in an LMI neighborhood and they could get to a wealthier wider neighborhood in 20 minutes on transportation, that’s equity. That’s how we look at equity here in San Diego, so.

San Diego is a city that draws people—it is important to build in a way that allows them to stay. Photo courtesy of Canva.

Affordable housing financing typically consists of a predevelopment loan, a construction loan, and a local source of funding. LISC San Diego provides the predevelopment loan to developers. Infographic created using Canva.

At the end of the day, we need to accommodate for different patterns of growth. And we also need to be able to create environments where people of different economic backgrounds and race and genders are all coming together.

Ricardo Flores, LISC San Diego Tweet

Iconic spots like the Gaslamp District are important to people, and can inspire calls for preservation, rather than development. An individual homeowner’s feelings about their neighborhood can be similar. Photo courtesy of Canva.

Designing streets to more safely accommodate bikers can encourage this alternative form of transportation. Photo courtesy of tttuna on iStock.

Chloe (11:58): Well, I know that the work that you’re doing it’s very collaborative, partnership-driven. What value does that approach bring and what possibilities and opportunities has it opened up for LISC San Diego?

Ricardo (12:09): Oh yeah, no. I mean, you can’t do it without partnerships. That’s the reality. I mean, you cannot… in the world that we work in—policy—if it’s your great idea and only you believe that, that’s not going to go very far. Because, you know, the public elected officials, everyone’s asked: who are your partners and why did, why are they a part of this, right? I mean, it’s the basic foundation kind of this country. Hey, you know, we’re going to get together and we’re going to fight for something that we think’s important, right? Redress our government on something. And so our partnerships are crucial to this. When we started this process, I, intentionally wanted to create a Black and Brown coalition because… we started this in 2017 because we were really interested in pushing the city council. And so we created a coalition that wanted to say, look. You guys, many of you people of color yourselves, are enforcing laws that actually wouldn’t have allowed you to live in parts of the city.

(13:09) And actually, maybe depending on where you live in your district, in your district! And your community! When a group like us says, look, you have an apartheid in your community. You have communities that are all white, all wealthier, better schools, better infrastructure. You have communities that just during COVID have not only been knocked back. We don’t know how far back they’ve been knocked, because we’re still dealing with COVID, right? We had to come together in a coalition in order to really define the issue and say that it’s, this is harming communities of color. And then that same coalition, like LISC—we work in these communities of color. That’s what we do. That’s our main source of, of attention. So we also had to be able to say that we can do our work if we allow individual families to move to other neighborhoods where we know—based upon a Berkeley study of the Belonging Institute last year—we know that if a family grows up, if a young person, grows up in a certain environment, that they’re gonna have a better lifetime earning potential, better healthcare outcomes, all of those things.

(14:16) And so should we not—as we continue to focus on neighborhoods and bring resources and funding and affordable housing—should we not also think about the opportunity to allow somebody from this neighborhood to live in another neighborhood if they see that as a better opportunity for them and their families? And the answer is yes, we should. And, and of course this all dovetails back to gentrification. Because all of us that are listening, you know, gentrification is not a two-way street. It’s a one-way street. It’s white, wealthier people or white, younger, white people living in Browner, Blacker neighborhoods. And I, I would see this when I’d walk in a community of opportunity, knock on the door, and a younger white family would come out. That’s what gentrification is. That white family lives in that neighborhood because that’s the only place they can see themselves purchasing, buying and living in the urban core. Where they would rather live would be probably another neighborhood.

(15:10) But that particular neighborhood’s not accommodating for their growth, right. That neighborhood says we’re off limits. And so again, this concept of being able to open up these, that 53% of the city—not only to people Brown and Black, but young white kids, young white professionals—that’s gonna allow groups like LISC and others to continue our work in these communities of concern in a much more intentional way. Because frankly, you know, I think we all know the story of redlining. That the government said, “don’t put money into these neighborhoods” to the private sector. I would like to better understand: what did the public sector do? Did they follow that after those maps were adopted? Like how much money were they giving to these neighborhoods? And how much did these neighborhoods not get funded for? Because we have to have an understanding here that a million dollars to put, you know, 200—let’s say trees—is a good thing.

(16:07) Don’t get me wrong. But that pales into comparison as to what has happened in those neighborhoods, right? It pales into comparison as to what challenges those neighborhoods face. And so let’s be realistic about that. Let’s not just use token amounts of money to say, “well, we’re doing what we can.” Until cities and jurisdictions intentionally go out and create bonds or new taxes and put that money intentionally into these redlined communities without ambiguity, right? With the full knowledge that we’re doing this because we did something wrong. Not this sort of, we’re gonna do it to everybody because everybody’s suffering. No, not everybody is suffering.

I'm really always fascinated that people will say to us: what do you mean there's no hoops that they have to jump through? You're just gonna give them money? Yes. Because you know what? These people have credit scores, they have jobs, they have savings, but they cannot put the down payment down.

Ricardo Flores, LISC San Diego Tweet

Chloe (16:51) Have there been pilots where there have been additional tax funds that are used towards equitable affordable housing?

Ricardo (17:00) I mean, we have, you know, even in our Climate Action Plan, they have an equity component that’s supposed to put funding into inner city neighborhoods for equity. I mean, there’s always that attempt, right? I mean our local government here is, is saying, okay, we’re gonna pave, you know, 200 miles or X amount of miles in these neighborhoods only, or we’re gonna add lights to this community. So you see that attempt to, to kind of nibble around the edges as I would say. But the damage and the challenge is so much greater than that. We found that the city of San Diego—in their Housing Element documents on affirmatively furthering fair housing—basically admitted in a document about the history of segregation from the time of the Spanish all the way to now, crazy enough.

(17:47) They actually said there was a conversation at the city council in 1923 where the goal was to take the covenants and to continue their enforcement, but through zoning. And then the other thing too is San Diego, like a lot of places just prior to the war, and then during World War II, built communities in order to support the war effort. And in our community it’s no different. And in fact, there were two integrated neighborhoods in the city of San Diego. One of them was destroyed by the city, essentially, and it’s where a sports arena now sits. And the other one is a community called Linda Vista, that’s still actually a community. But they destroyed the one at the sports arena purposefully because the community around there did not want, you know, did not want folks there. And so we want to ask the city, because now the city is saying: okay, we’re going to lease this big piece of land out and we’re going to build housing and build a new sports arena and create this entertainment complex… and all this stuff.

(18:45) Well, if the cities took it from people of color and it was the only integrated neighborhood, why can’t they provide that land back to a program like ours, so we can provide that to homeowners without paying the land costs? And then the second question we’re going to be asking is, you know, what is your intention? What did the city do with respect to after redlining, in terms of its investments in communities? And can we track that investment over time? Because we need to understand what they did and how little investment was actually put into these neighborhoods. Because right now, again, we’re all going off of assumptions as to what happened here and we need to get a better picture.

Kaylee (19:21): I was just going to say, I saw on your website that you have the, the Redlining in San Diego map project. Was that sort of a start at getting the answers to some of these questions you have?

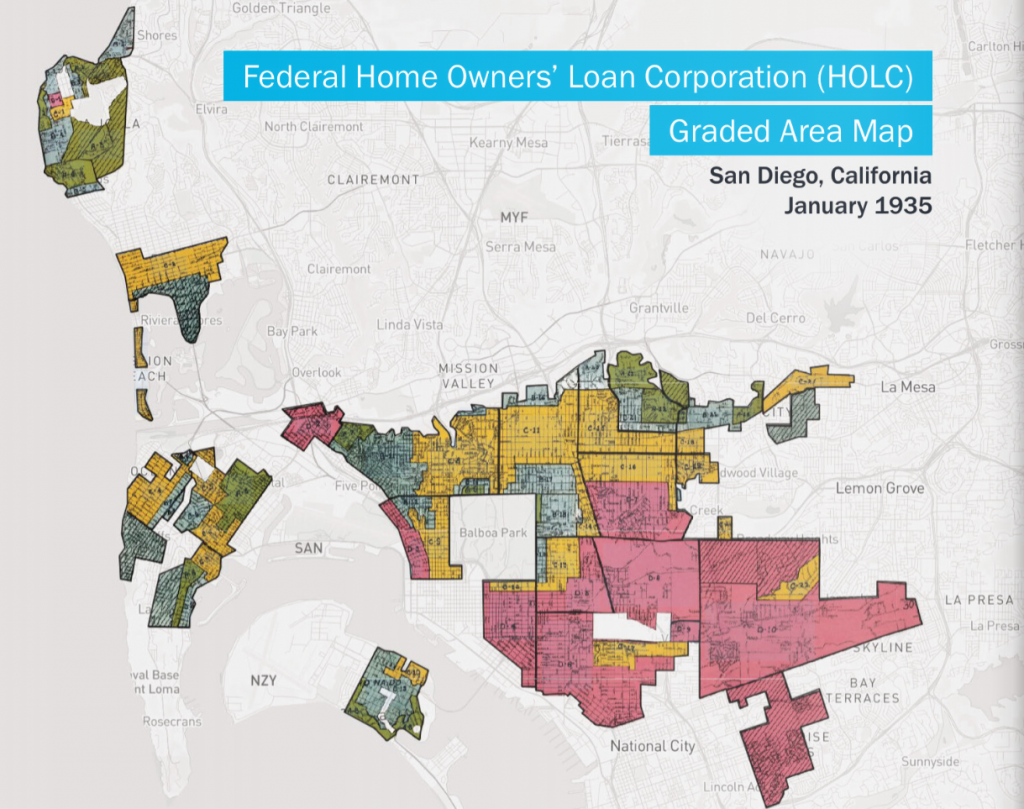

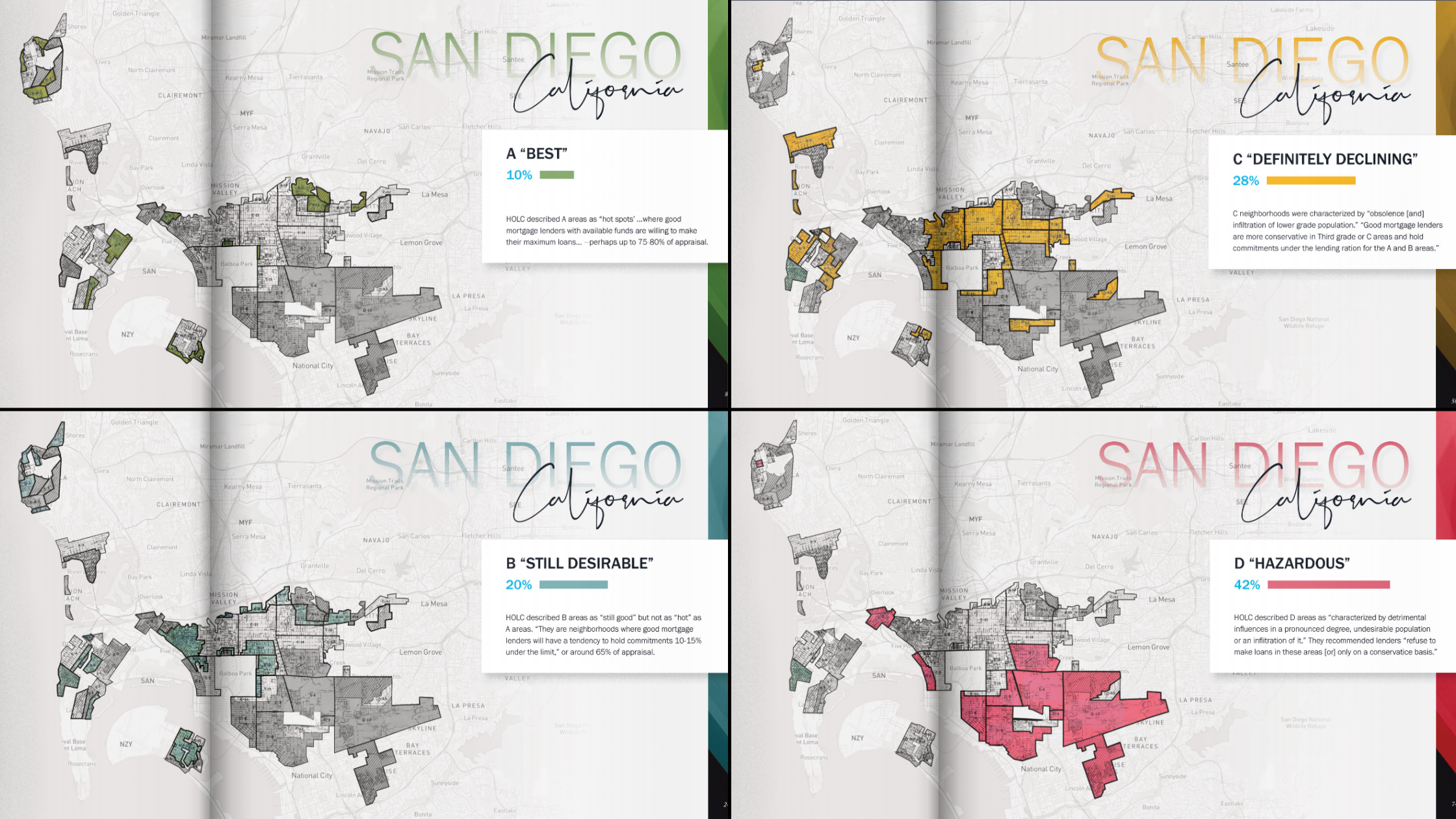

Ricardo (19:29): Yeah, so it’s interesting. I had learned that the University of Richmond, Virginia… in like 2016, it put all the redlining maps… They digitized them all. They didn’t put them together. They just had them where you could, like, download them on its own. So I thought, well, you know what? Let’s just put it together for our region. And let’s see what it says. And you know, for people that are interested in this work, it’s really interesting to read. Because it gives you kind of an interesting background about, you know, the age of the housing in this community, what it looked like, who lived there… kind of the amount of money they made. It says that this is a good neighborhood because of this thing called R1 zoning. So as Richard Rothstein says, it is admitting it is violating the Constitution.

(20:14) They’re just saying it right then and there—we’re violating it and this is why we’re doing it. And so what I like to tell folks about the redlining maps is they’re a point in time. Because a lot of people get confused and say, oh, well, redlining’s gone, Ricardo. Deed restrictions are gone. Why are you… what’s going on with you? Why are you making such a big fuss about this? Because they are technically gone. The ramifications are still with us. But zoning hasn’t gone away, and zoning is still enforced. And, and so what the redlining maps do is they create a point in time. So now in San Diego, I can look back almost a hundred years and I can say, what did this community look like? Who lived here? What was the value of the homes? And it’s just so canny, because that same community where poor people and people of color lived in, they still live in and they’re still poor.

The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) produced maps of every city and assigned ‘risk grades’ to neighborhoods from A-D. Green neighborhoods were considered the best (A), and red hazardous (D). Image courtesy of the Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America – San Diego project.

Cities and jurisdictions [need to] intentionally go out and create bonds or new taxes and put that money intentionally into these redlined communities without ambiguity... With the full knowledge that [they're] doing this because [they] did something wrong.

Ricardo Flores, LISC San Diego Tweet

(21:03) And they’re still people of color. So yes. Let’s keep providing Section 8 and all these other resources—that’s good stuff, too. But let’s allow people to live in neighborhoods that work. And I’m 45. I’ve lived in San Diego my whole life. So what are you gonna put all those taxpayer dollars into—the world that I grew up in? Or are you gonna do it to a world that we haven’t yet built—to the future? Because if you’re planning to put all that money into the world that I grew up in for the past 45 years, you’re going to make serious mistakes. And all for what? Because 53% of the city of San Diego doesn’t want to have any new construction in their neighborhoods? They want to have their home smack dab in the middle of 5,000 square feet with a front lawn and a backyard? But again, we’re trying to tell politicians if you subdivide those lands, you can go back to those property owners and you can actually say, look, you’re going to benefit from this.

(21:59) Believe it or not. Because right now you can sell your land and your home for one value or one payment. But if you subdivide, you can do four payments. And even when I explain that to people in these neighborhoods, they still don’t like this idea. Because again, it’s never been about common sense. It’s been about keeping their neighborhoods whiter and wealthier. Exclusive, right? If I, with all my college degrees, live in this neighborhood, and somehow my cousin who has his degree from high school is now living next door to me, then how am I more exclusive than him? Right? We’ve created this world where where I live shows part of my exclusivity. And so again, we, we have to be cognizant that people deserve opportunities and that… the idea that you’re gonna exclude individuals because of whatever concerns you may have internally? That’s unacceptable.

Chloe (22:53): I know we have just a few minutes left, so I really would love to reintroduce the word regenerative to you. We’re using this term a lot in our work, in that going beyond sustainability, we need to revitalize our communities and our environment. What does regenerative mean to you, and how might that term apply to your work?

Ricardo (23:14): Yeah, I mean, I think we’re in a regenerative phase in our community, where we’re in an inflection point. The San Diego that I grew up in is still very much relevant to the world that I see, but the demands of San Diego are much different. You know, we’ve got more people living here. We’ve got more diversity now. We’ve got different industries now. We are a place people want to live. And I think that regenerative means really rethinking what communities look like, and really loosening restrictions so that we can see these communities kind of fill in and be able to accommodate growth. And so I think it’s a good time, to be honest with you. In fact, here in San Diego, a group of students at the University of California, San Diego have been involved with the local planning group in La Jolla, so much so that they actually, during this redistricting process, wanted out of that district. The youth from the college.

(24:11) Now I went to UCLA. The last thing I would’ve joined was the planning group in Westwood. (laughs) Again, you’ve got such a challenge ahead of us that you’ve got young people taking time out of their education and having fun to join planning group meetings with baby boomers who could be their grandparents and are refusing to build more housing in their neighborhoods because, quote, that’s the way it was for them. (laughs) I mean, you can’t make this stuff up. (laughs) So I think it’s a good time. I think it’s a positive moment. I think we’re gonna get some change that we need. Because ultimately, I don’t believe… at least here in Southern California, I don’t believe that they understand that local government controls the value of land. They think that this housing market is so complex, so difficult, and they don’t see that actually, the value of land is what the city council can best determine. So that, to me, is what makes me hopeful. Because when people are not seeing that nexus and yet we clearly are—and our colleagues are—that gives us political opportunity.

Neighborhoods with an A rating were seen as hot spots lenders should target, while those with a D rating were seen as areas to avoid. Neighborhoods with higher ratings were invested in more heavily over time. Image courtesy of the Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America – San Diego project.

Chloe (25:20): Definitely. I’m hoping to get some recommendations from you on how someone can get involved with LISC San Diego. We’d love to plug the work that you’re doing and elevate it with our community.

Ricardo (25:32): Yeah, no, please. You know, reach out to me with my email, [email protected], L-I-S-C.org. And then of course, you know, we’d love to get folks to help us, support us. If you’re an organization and you think what we’re doing is incredible, say, “hey, we’ll endorse that.” Because we have a lot of endorsements. We would love to be able to share, “Hey, we’re, we’re making an impact outside of our region.” And then of course the last thing is, you know, if anybody’s listening to this and has a lot of disposable income or a company they work with and wants to provide home ownership to Black families, you know, Black wealth, here’s your opportunity. We have a program with mortgages attached and it works. It actually works, and we’ve got 19 homeowners right now.

(26:14) And so allow us to keep doing this because, again, there’s a group of people out there that can be homeowners. They’ve played by the rules, they have savings, they have a certain credit score… all of these great things that we ask folks to do. So yeah, we’d love to have people join us on this interesting journey, because it’s fascinating to me that we’re talking like this and that we’re one of the few groups that are so passionate about looking at land and saying, let’s just not just build four units or five units or six, but let’s subdivide to provide home ownership. And then lastly, if you’re from these neighborhoods that we’ve been talking about here, you should feel good. Because what we’re really saying here on this conversation is: your neighborhoods are so incredible. They’re so beautiful. They have so many good things happening in them.

(26:59) We just want others to experience that. Right? That’s what we’re saying. If it’s like a restaurant with good food, we’re just saying everybody wants to try some of that. That’s all we’re saying. So let’s be cognizant that this is a good problem that we have here in our communities. It means people want to live here. It’s a good thing. It’s a positive thing. People come here to get an education, experience our culture, our community… and then they leave. And they make all their money and all their stuff somewhere else. We want them to stay. We want them to stay and do it here. Right? We have every incentive for them to stay here. Why not?

How can you get involved?

Follow LISC San Diego on social media

This vibrant space in San Diego, with people walking, biking, and shopping, represents the types of spaces we can work to build everywhere. Photo courtesy of Canva.

Newsletter header image courtesy of tttuna on iStock.