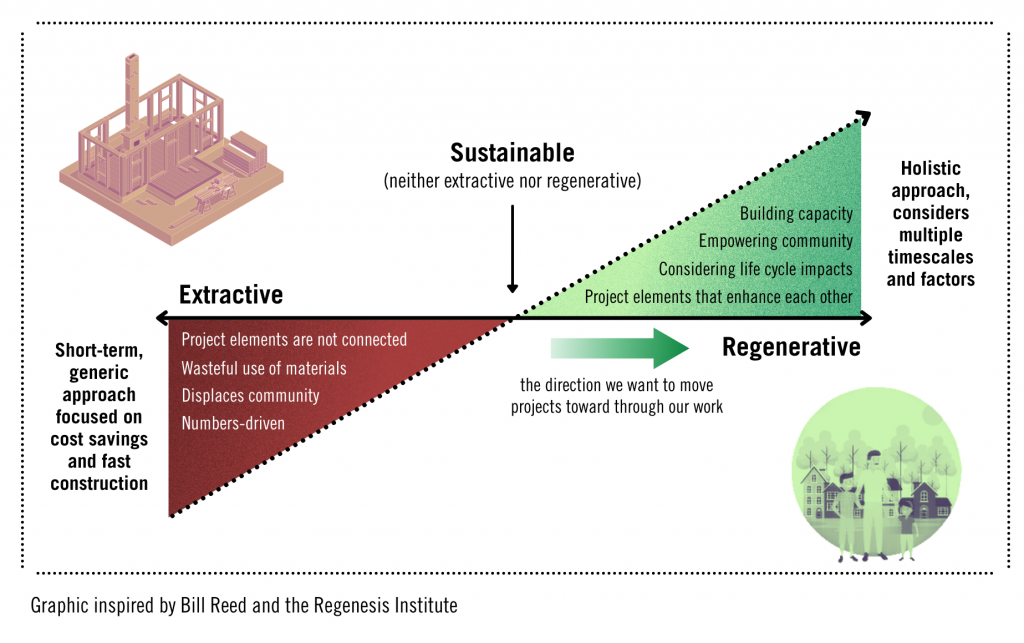

The projects featured in our Neighborhood Insights series demonstrate an intentional, holistic approach to shaping the places where we live. It’s not just about project results, whether they be solar panels and green spaces or local jobs and permanently affordable housing. It’s about the processes, collaboration, community leadership, and care that go into achieving those results. Through this series, we hope to show that we can all aspire to something beyond ‘sustainable and affordable’—collectively, we can start to envision developments that revitalize communities, restore ecosystems, and give places the ability to evolve and adapt to whatever changes the future holds.

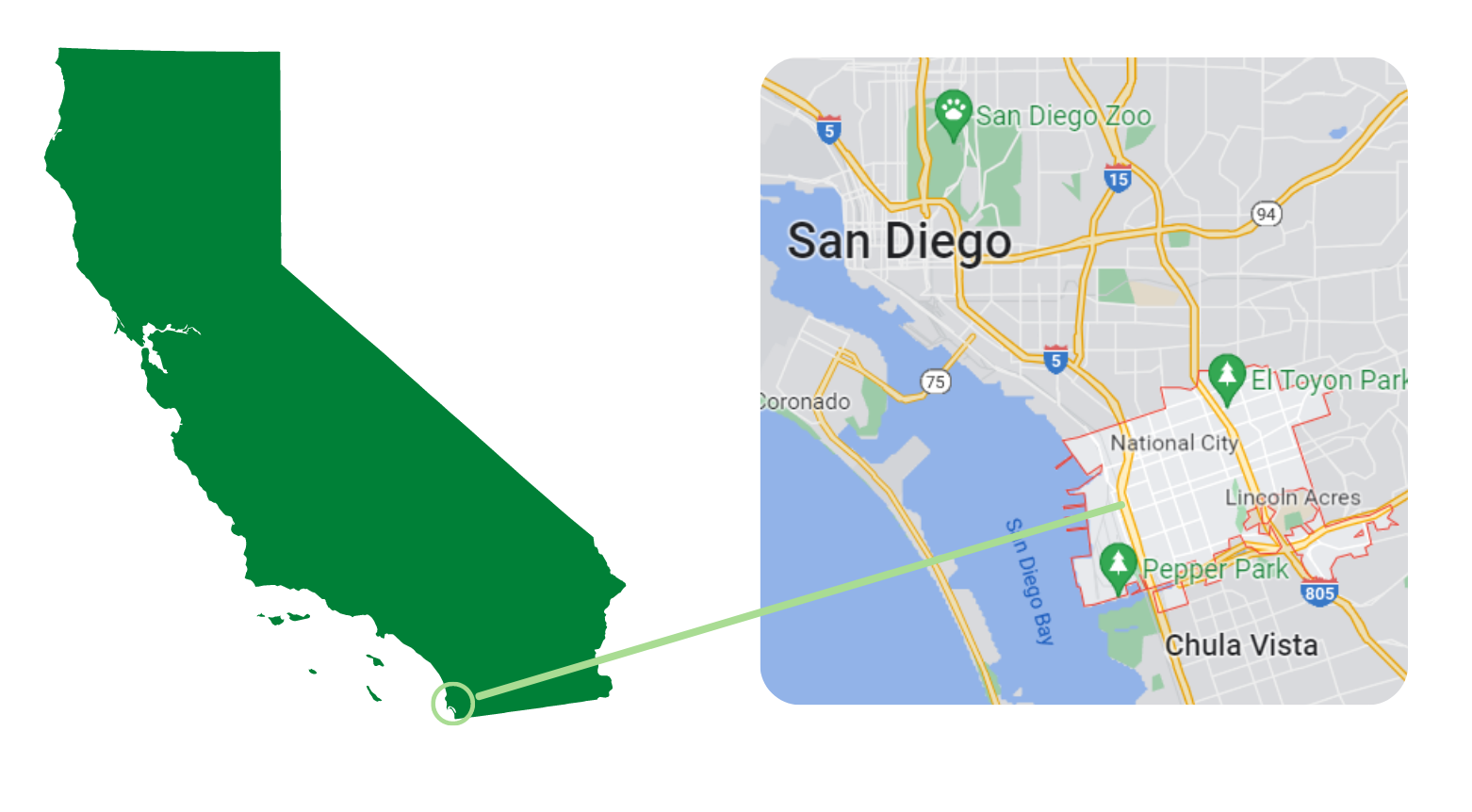

The 24th Street Transit Oriented Development Overlay (TODO project for short) is a plan designed to revitalize a 760-acre area near the 24th Street Transit Center in National City, California. The assessment phase of the project started in 2019, which set the stage for developing recommendations and the plan itself in 2020 and 2021. Each phase was interspersed with community engagement workshops and stakeholder meetings to ensure that what was being created reflected areas of importance for residents, including: improving neighborhood connectivity, creating opportunities for increased housing development, and shaping a more vibrant neighborhood with a variety of land uses.

The project team is currently in the process of securing additional funding for implementation and has put together a list of programs they might pursue here.

National City sits on the lands of the Kumeyaay people, who established villages in the geographical area spanning approximately from Oceanside, California, to Ensenada, Mexico. Graphic designed in Canva.

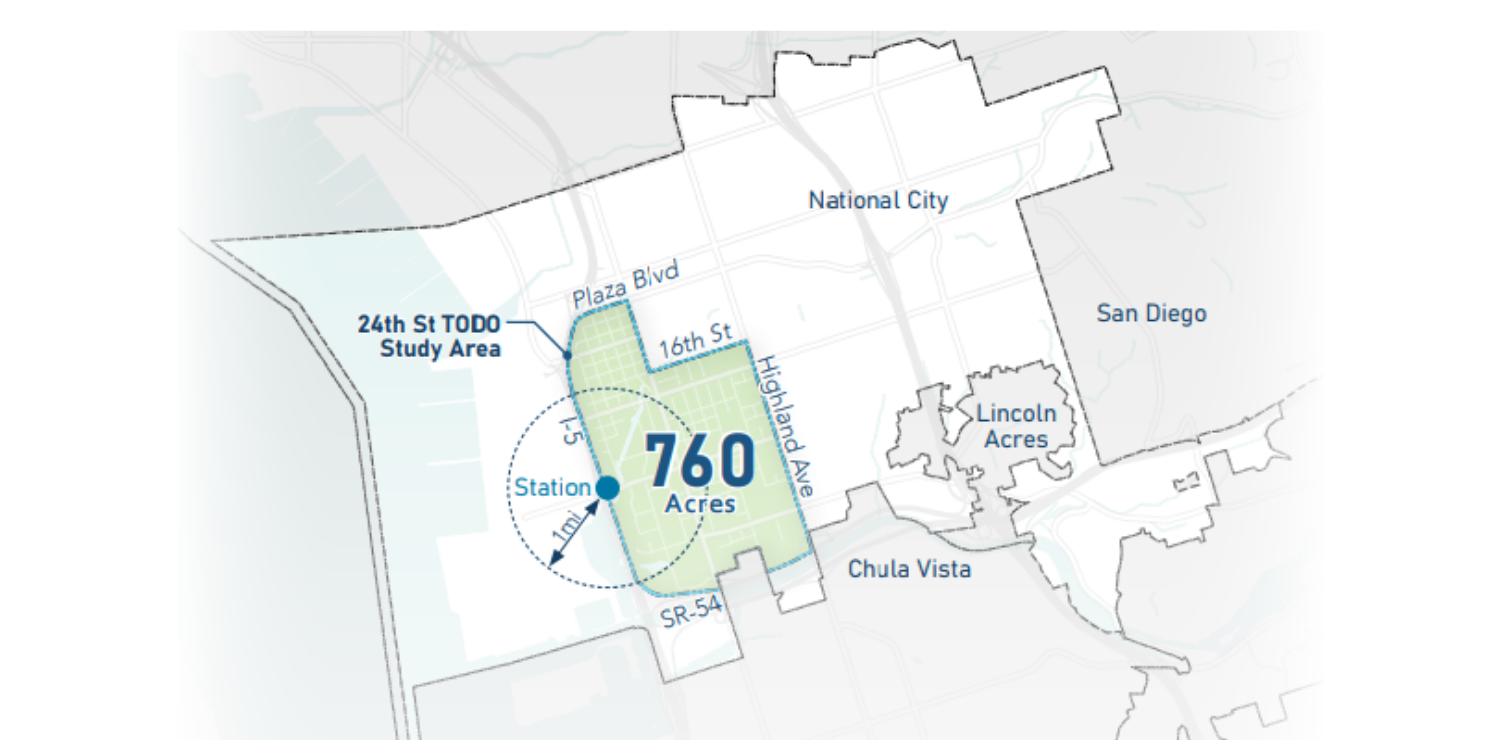

The TODO project area, shown in green above, is located near National City’s 24th Street Transit Center and bordered by Interstate 5, State Route 54, Plaza Boulevard, 16th Street, and Highland Avenue.

The TODO project proposes a holistic, multi-step approach to achieving a 10-minute neighborhood—one that is walkable, bikeable, and offers everything a resident might need within a small radius. In light of the area’s history of auto- and industry-focused development, it is committed to doing so in a way that centers restoration, resident health, and rebuilding.

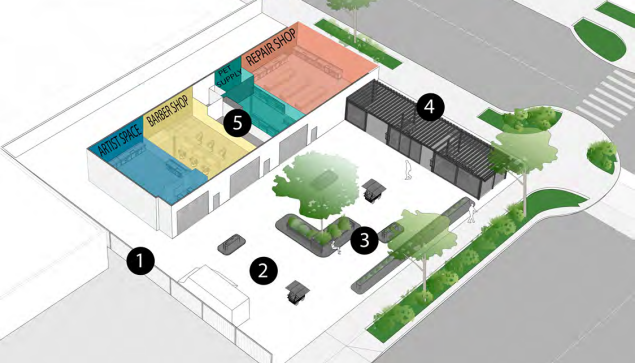

Many of the plan’s recommendations focus on leveraging the area’s mix of land uses to provide amenities, services, and additional housing in close proximity. To this end, the plan proposes several development prototypes, such as: ribbon screens to create visual separation between different land uses and the street, “pencil” towers to build in a high-density, low-sprawl way, and adaptive reuse of warehouses, parking lots, and underutilized buildings to provide facilities that better serve residents. By developing new homes on infill lots and repurposing existing structures for new uses, residents will be able to go to one area and fulfill a number of their needs, from shopping and getting a haircut to taking educational courses. This not only encourages local investment and economic growth, but saves residents travel time and money—a change that helps them build the capacity to invest in themselves.

Achieving a 10-minute neighborhood also means strengthening the area’s transportation network and investing in infrastructure that better accommodates bikers and pedestrians. These improvements will allow residents to get around without relying on a personal vehicle and make important destinations, like the 24th Street Transit Center, much more accessible. Street redesign and improvements like multi-use paths also provide opportunities to integrate artwork and greenery that enrich public spaces and better reflect National City’s culture.

By improving connectivity across the project area, residents will be able to make better use of existing bike- and pedestrian-friendly infrastructure.

Adaptive reuse is a development strategy in which underutilized structures are repurposed into new buildings. This graphic shows how it could be applied to development in the TODO project area.

This concept of a mobility hub demonstrates how infrastructure can encourage different forms of transportation within a neighborhood.

Aside from the vision itself, what makes the TODO project unique is the breadth of public outreach involved in the visioning and planning process. To achieve a plan aligned with resident priorities, the TODO project team held four virtual workshops, distributed two surveys that received 190 responses from the surrounding community, and set up meetings with property owners, public agencies, and local non-profit organizations in the study area and National City. By providing multiple engagement formats and bilingual materials, the team was able to meet their goal of sourcing feedback from a wide variety of stakeholders.

To understand the importance of the TODO project, one must consider some of the ways in which the project area was disinvested over time.

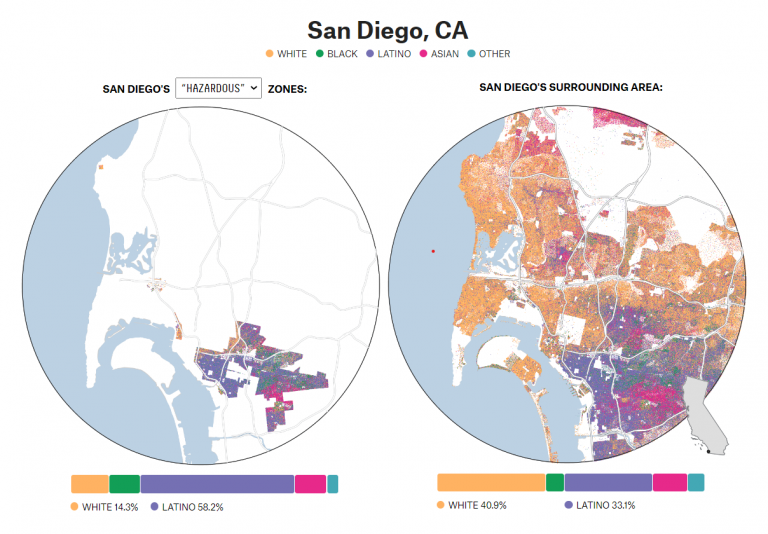

National City is located in the South Bay region of the San Diego metropolitan area. The San Diego neighborhoods historically considered “high risk” for investment have large Latino populations, with HOLC appraisals often using words like “infiltration” and “lower social strata” in reference to Latino population growth in communities.

When HOLC became active, exclusionary zoning and racist ideologies had already driven the creation of exclusive, white single-family neighborhoods. Non-white racial groups were restricted in where they could live, and the neighborhoods that were accessible to them permitted industrial land uses. Once redlining maps were created, this gap intensified. Predominantly white neighborhoods—seen as safe for lending and best for investment—were readily financed and saw increases in homeownership over time. Non-white communities and their residents were denied those same growth and wealth-building opportunities.

The map of San Diego’s surrounding area shown below highlights the lasting impacts of these discriminatory housing decisions. Though enacted just a few generations ago, these policies have created a persistent gap in wealth and resources between the communities that were redlined and those that were not. National City, which is fairly adjacent to the “hazardous” zones, reflects the strength of this segregation—today, its population remains predominantly Latino and Asian (60 percent and 20 percent respectively).

About the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation

In the late 1930s, a government lending agency called the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) launched a national initiative to determine mortgage-lending risk all the way down to the neighborhood level.

HOLC officials would assign neighborhoods grades from A-D, with an “A” or “Safe” rating indicating the area was prime for investment, and a “D” or “Hazardous” rating indicating a neighborhood where residents were likely to default on mortgage loans. Areas deemed safe were predominantly occupied by white Americans, and those considered hazardous for investment were predominantly occupied by non-white racial groups.

While the HOLC redlining map for National City was not one of those digitized through the University of Richmond’s Mapping Inequality project, FiveThirtyEight shared a series of maps earlier this year that explore the demographics of redlined communities and their surrounding areas today.

Some of the area’s recent revitalization efforts, like the Paradise Creek Apartments, have focused on addressing these injustices and building in a way that centers community needs around housing, resources, and the remediation of industrial contamination. Others are focused on celebrating and emphasizing National City’s vibrant culture. The TODO project is doing its part to shape a district where residents can thrive by identifying strategies that are guided by and respond to community priorities.

The mobility section of the plan focuses on making streets safer, bolstering pedestrian and cycling networks, and increasing the connectivity of the area’s transportation networks to key locations. These changes will help improve safe access to existing facilities and opportunities and reduce car-related emissions.

As a starting point, the plan recommends a slew of improvements at intersections for pedestrian safety, such as high-visibility crosswalks and countdown signals. After achieving this baseline, the focus can shift to improving popular streets in a way that encourages safer multimodal transportation. Many of the recommendations here include building out sidewalks, creating larger buffers for bike lanes, adding landscaping, and incorporating infrastructure that permits stormwater recapture. These are also opportunities to incorporate artistic touches that help reshape the neighborhood’s character in a way that is truly representative of its residents.

The plan also explores how to improve highway undercrossings, whether that’s through the development of multi-use, car-free paths or a potential bridge for pedestrians and cyclists. Freeway development has historically been used to break up and disrupt redlined communities, so exploring how connectivity across them can be restored is another way the TODO project is working to address past injustices.

Supporting safe multimodal transit on busy streets like D Avenue, shown here, is a key focus of the TODO project.

This I-5 undercrossing revitalization concept is an example of how the disruption caused by historical highway development can be mitigated.

The project area has several infill lots that could support small-scale developments, like accessory dwelling units, bungalow courts, duplexes, and townhomes. Due to their size, these homes tend to be more affordable, easier to integrate into existing neighborhoods, and more flexible in terms of where they can be constructed. There are also large lots south of the 24th Street Transit Station with the potential to support larger multifamily buildings, as well as a few streets and corridors that are prime locations for mixed-use residential development.

The TODO project also explores the idea of transition areas. By taking advantage of landscaping and existing buffer zones like alleys, these areas can create a separation between homes and industrial land uses. This is an important step toward addressing the area’s lasting environmental justice impacts and establishing a standard of centering resident well-being in decisions around development.

Lastly, the Paradise Creek Gateway District is a land use recommendation that proposes combining the Paradise Creek Educational Park, Paradise Creek Apartments, and Paradise Creek itself into a larger district. In bringing these three areas together, this concept builds on revitalization efforts the community has been driving for decades.

For example, the Paradise Creek Educational Park is the result of dedicated residents working to restore Paradise Creek into a space for education and gathering back in the 1990s. This vision was achieved in 2007, and since then, the creek has become a central part of the community that connects residents more tangibly to the area in which they live. Its large geographical span also creates an opportunity for greater connectivity across the city if development is pursued nearby.

Similarly, the LEED-certified Paradise Creek Apartments—which brought 201 affordable, energy-efficient homes and a new public park to the community—started with community leader advocacy in 2005. The development not only addressed health concerns through contamination remediation efforts, but created homes near transit, job opportunities, and open space. The Paradise Creek Gateway District would bring these community accomplishments together in a way that becomes a focal point for the broader city.

The Paradise Creek Educational Park, built around the restored Paradise Creek, is an important space for community gathering and education. Image courtesy of Martin Reeder.

Alex Coba

Communication Associate

As a proud California native from Stockton, Alex brings a wealth of experience and a versatile skill set. He has a solid communication background with a Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Public Relations from California State University, Chico. Alex is adept at strategic communications and media relations, with experience gathering and sharing stories from his local communities that uplift the unique spirit and values of those places. He is excited to join Build It Green, where he can apply his talents to further BIG’s mission to help communities across California thrive