© builditgreen.org 2024 | All Rights Reserved | Site by JoomDev

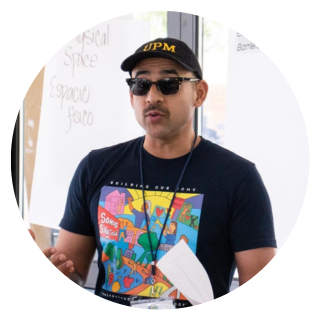

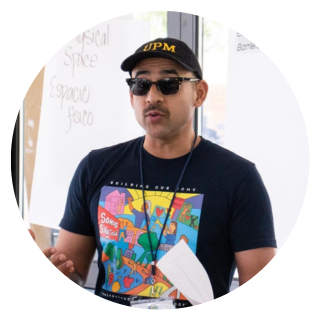

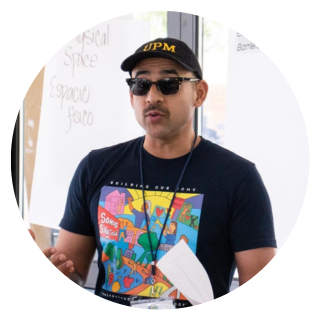

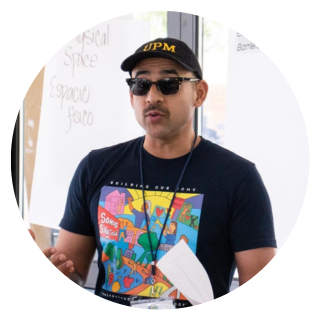

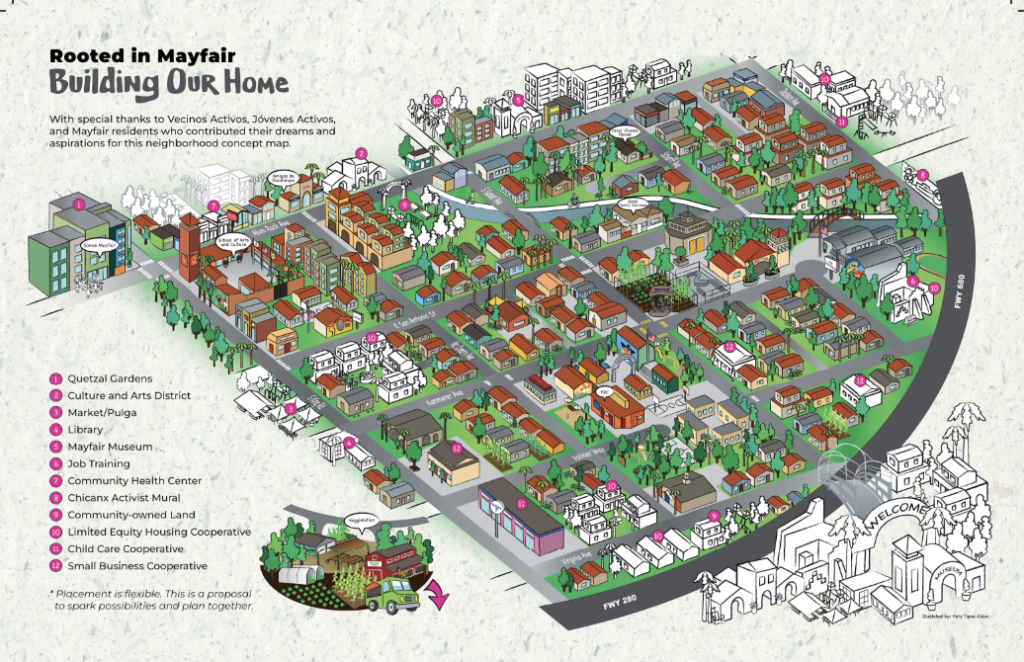

The residents of Mayfair, including youth, elders, and neighbors, have come together to create the Community Vision Map of Mayfair. This map envisions a bright future for the neighborhood, including murals, cooperative businesses, cooperative childcare, accessible health clinics, libraries, outdoor space, and limited equity housing cooperatives. Paty Tapia-Colon, a local artist, compiled feedback from the community to create the Community Vision Map of Mayfair.

Build It Green connects changemakers to transform the housing system in service of human and ecological vitality.

1 (510) 590-3360

Mon – Fri, 9am-5pm

[email protected]

© builditgreen.org 2024 | All Rights Reserved | Site by JoomDev