© builditgreen.org 2024 | All Rights Reserved | Site by JoomDev

What is equitable housing decarbonization?

This seemingly straightforward question often came up during discussions in our Affordable, Equitable Decarbonization Working Group.

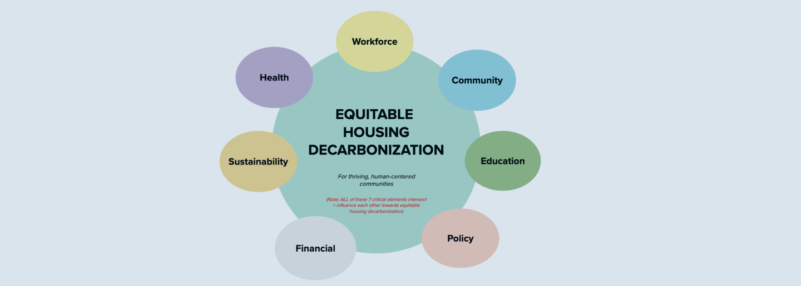

To start a dialogue, BIG offered space to develop, with the working group and other partners, a visual diagram.

We aimed to communicate the intersections and visions communities need to succeed in lowering homes’ carbon impacts and reach equitable outcomes.

In developing our Equitable Housing Decarbonization Diagram, we hone in on seven critical elements that influence and intersect with each other. These seven critical elements are:

We hope this diagram can demystify, empower, and connect the dots on how different stakeholders can engage in working towards equitable housing decarbonization.

Whether the stakeholder is a student, renter, homeowner, architect, contractor, developer, educator, policymaker, or financial institution, the changemaker may engage with one element primarily, or multiple elements simultaneously. We hope this diagram will facilitate the intersectional mindset and pathways essential for holistic equitable housing decarbonization efforts. Dive below to learn more about these seven elements.

When we decarbonize homes, existing communities should thrive. Residents should be able to continue living in their homes and realize the sustainability, financial, and health benefits in decarbonization. No one is unhoused, historically excluded populations are intentionally supported with culturally accessible resources, and future generations are provided for.

At the same time, communities have agency and democratic governance to shape their journey, make informed choices, and support and invest in their local workforce.

Decarbonization strategies are only effective with an informed public that understands and can leverage those strategies. This informed public includes communities, the workforce (from architects to contractors), policymakers, and government officials.

This section considers on-the-ground training for policymakers; trusted community avenues to share technical knowledge; and continuing education for workers about low cost decarbonization strategies.

The financial sector needs a complete system change to support an equitable future – agencies working together, banks supporting zero carbon housing, banks divesting from fossil fuels, and of course accessible, creative fair loan programs.

We must simultaneously grow the funding sources and incentivize decarbonization. These incentives should support contractors to sustain quality careers (which directly relates to the workforce element).

Above all, our financial systems must prioritize disinvested communities through engaging with community members as technical experts and supporting low-income homes, which are most vulnerable to increasing utility bills.

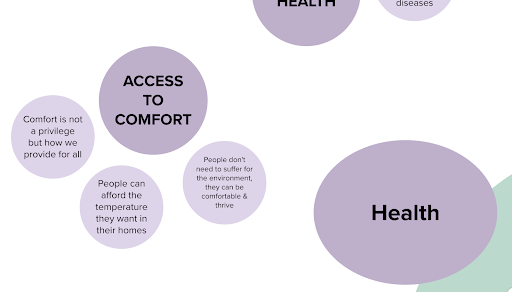

We envision people living comfortably in their homes as a fundamental right. In this ideal reality, people live at ease – physically, mentally, and financially – in their sustainable homes, newly built or renovated, as a safe harbor through extreme weather events like heat waves.

No one should have to sacrifice their physical health and be energy insecure because they do not have the financial means; we can support having homes passively maintain temperatures at reasonable costs.

A passive home is a home that is structurally designed to manage its temperature, for example, without relying on air conditioning to keep cool. Instead, a passive home would use insulation, building materials, home orientation, windows, and more to help control temperature.

In order to achieve equitable housing decarbonization, the easy and legal choice also has to be the environmentally good choice.

The framework of policy and program design should be outcomes focused to not only support and incentivize zero carbon homes, but maintain and strengthen the community fabric through tenant protections, quality labor standards, and educated and trained local officials.

This diagram encourages us to look beyond surface-level sustainability and instead catapults us to consider the many elements needed to create thriving communities.

For example, we will power homes with safe, clean sources that have minimal impacts on resident’s health; the home’s building material will be safe and carbon-free; biking, walking, and other alternative transportation modes will be safe, encouraged, and accessible while supporting a lower neighborhood carbon footprint; and we preserve our existing homes and make them healthier, safer, and adaptable to survive climate change.

California faces a contractors shortage from carpenters, electricians, plumbers, and general contractors to build and maintain our homes; and these workers are essential to decarbonize our homes and support an equitable transition to clean energy. We need to be intentional and thoughtful as we increase the workforce supply and demand. When we provide abundant pathways to train more workers, we need to ensure it is accessible in disinvested communities. Then, as policy and education incentivizes and increases demand for these workers, we need to ensure the increased jobs and small businesses are formed with baseline labor standards that respect workers’ voices, a living wage with benefits, and a culture that supports women and BIPOC folks.

When considered together, these seven essential elements to housing decarbonization have the potential to support more integrated, equitable work overall. If you have questions about this resource or would like to get involved with BIG’s Affordable, Equitable Decarbonization working group, please contact [email protected].

Build It Green connects changemakers to transform the housing system in service of human and ecological vitality.

1 (510) 590-3360

Mon – Fri, 9am-5pm

[email protected]

© builditgreen.org 2024 | All Rights Reserved | Site by JoomDev